Albumin is a protein which plays multiple functions in the human body, such as maintenance of colloid osmotic pressure (COP), carrier of molecules, scavenger of oxygen-derived free radical species in sites of inflammation, participation in the acid-base balance, contributor to waste product elimination and mediator of coagulation. Increased albumin loss may be due to multiple aetiologies commonly caused by abnormalities of the gastrointestinal and renal systems, while albumin redistribution may be caused by inflammatory states, sepsis and burns. Hypoalbuminemia is frequently associated with protein-losing enteropathy (PLE), whose well-known aetiologies include congenital cardiac disease, mucosal and non-mucosal gastrointestinal diseases, and lymphatic abnormalities [1]. Adverse reactions to human serum albumin (HSA) are infrequent and the pathogenesis is not entirely clear. Skin prick tests are performed with full-strength solution of albumin. As for the intradermal tests, 1 : 10 and 1 : 100 dilutions, obtained from the full-strength solution, are commonly used on an empirical basis. However, according to the literature, the sensibility of these skin tests remains to be assessed. In patients with a history suggestive of hypersensitivity reaction (HSR), rapid desensitization protocols have been described and proved effective [2]. This desensitization approach is based on intravenous infusion of albumin at increasing doses. This report describes the evaluation of a patient who experiences a HSR to albumin and was successfully treated with a rapid desensitization protocol, adapted from Castells [3].

A 28-year-old female patient affected by primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL), congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF), transposition of the great arteries (TGA) surgically corrected at the age of 5, Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve (EA), and Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT). Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare disorder characterized by dilated intestinal lacteals resulting in lymph leakage into the small bowel lumen and responsible for protein-losing enteropathy that leads to lymphopenia, hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia [4]. In order to restore the albumin level, she has been infused two times Grifols (human albumin) 20 g/100 ml, but during the last administration she experienced fever, dyspnoea, severe hypotensive state, erythematous rash, which required treatment with systemic corticosteroids, antihistamines and hospitalization. She has also been infused Baxter albumin 250 g/l, with similar symptoms.

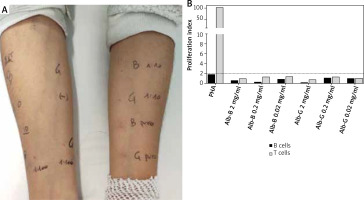

Although there are no validated skin testing for human serum albumin (HSA) in the literature, making the diagnosis of allergy challenging [5], we decided to perform skin prick tests with full-strength solution of albumin plus a normal saline and histamine phosphate control (10 mg/ml), and intradermal tests with the following dilutions 1/100, 1/10 and full-strength solution [6]. Reactions were interpreted after 15 min. However, all skin tests showed to be negative for all the concentrations used, as reported in Figures 1 A, B.

Figure 1

A – Skin prick test and intradermal tests with Grifols and Baxter albumin preparations; B – Flow cytometrybased proliferation assay

The case was further investigated using the flow cytometry-based proliferation assay. Freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells of the patient were stained for 5 min with Carboxyfluorescein (2 mg/ml, 0.2 mg/ml and 0.02 mg/ml). Cells incubated with phytohemagglutinin A (PHA) or no stimuli were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. All cultures were performed in triplicates. At the end of the 5th day of incubation, cells were harvested, washed and stained with fluorochrome-coupled anti-CD3 and anti-CD19 antibodies to distinguish between T and B cells, respectively, then analysed using a flow cytometer [7]. Using this technique, we can measure the percentage of proliferated B and T cells: indeed, proliferating cells have a reduced CFSE intensity as compared to resting cells. The test is deemed positive if the B cell or T cell proliferation rate of any of the drug concentrations tested equals or exceeds 2, as compared to the negative control.

Considering the necessity to treatment maintenance [8], despite the obtained results, an 8-step desensitization protocol, with an infusion time of 20–30 min per step, was therefore prepared with only two solutions: Solution A – Grifols (human albumin) 20 g/100 ml and Solution B – 10 ml of solution A in 90 ml of the physiological solution (2 g/100 ml) (Table 1). Indeed, according to the literature, it has been demonstrated that when human basophils are incubated with suboptimal doses of the allergen, they reach the minimum responsiveness in a time range between 15 and 30 min [9]. The target dose of 20 g was successfully achieved within 205 min. The protocol was performed without any premedication and did not report the same adverse effects that the patient had previously described. Overall the desensitization procedure was well tolerated, only a few wheals appeared during the final step of the first desensitization. However, we continued the infusion and completed the entire administration. Furthermore, an increase in albumin levels of 0.4 mg/dl was recorded, confirming the efficacy of replacement therapy despite following this desensitization protocol. In order to fulfil the patient’s needs and speed up the time of therapy as much as possible, a new protocol was designed made only by a 4 step-approach and without any diluted preparation, respecting the infusion speed limit, as stated by the leaflet (Table 2). Also in this case, no major adverse reactions were recorded and the patient can now be infused albumin following this scheme.

Table 1

Complete desensitization protocol (8 steps)

Table 2

Rapid desensitization protocol (4 steps)

| Steps | Concentration [g/ml] | Rate [ml/h] | Infusion time [min] | Volume [ml] | Dose [g] | Cumulative dose [g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20/100 | 30 | 20 | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 20/100 | 40 | 30 | 20 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 | 20/100 | 45 | 30 | 22.5 | 4.5 | 10.5 |

| 4 | 20/100 | 50 | 60 | 47.5 | 9.5 | 20 |

Adverse reactions to human serum albumin (HSA) are uncommon but approximately one-third of such reactions may be life-threatening. The incidence of anaphylactoid reactions to HSA has been reported to be 0.011% [10]. The pathogenesis of systemic reactions to albumin has not yet been better clarified. Some anaphylactoid reactions have been attributed to albumin aggregates or protein stabilizers, such as caprylate [11].

In the case described above, skin tests and the flow cytometry-based proliferation assay were negative, nonetheless we carried out the desensitization in consideration of the clinical features of the case, typical of a hypersensitivity reaction (HSR). The clinical manifestations of immediate HSRs vary considerably, ranging from mild to severe, with mucocutaneous, respiratory and cardiac symptoms. A serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) was initially hypothesized, but type III reactions are rare and also the pathogenesis is not really clear [3].

Jung et al. [12] demonstrated a new 10-step one-solution desensitization protocol using antihistamine and leukotriene receptor antagonist as premedications, which was effective and safe in a 13-year-old boy with albumin hypersensitivity. The total infusion time was 314.9 min, but the cumulative dose was only 2000 mg.

According to the literature, we believe that the predictive value of the skin tests remains ambiguous, in fact during the first administration of the desensitization protocol the patient developed mild urticaria lesions, suggesting that the adverse reaction was allergological in nature. The negativity of the described tests might be explained by different reasons: (i) the lack of standardization with skin tests to albumin, so the concentration used might have been not sufficient enough to elicit a valid response, and the possibility of obtaining false positives and false negatives; (ii) other immune mechanisms could be involved, not necessarily IgE-mediated.

In conclusion: (i) the desensitization protocol proposed proved to be safe and effective; (ii) a larger cohort of patients is required to enhance the diagnostic power of skin tests. Further studies may lead to a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of anaphylactoid reactions to blood products.