Introduction

Uterine fibroids represent the most prevalent benign neoplasm of the uterus and constitute a significant source of morbidity among women of reproductive age, affecting up to 68.6% of this demographic [1]. The main risk factors identified are premenopausal age, black race, nulliparity, and the time since the last birth [2]. Roughly 30% of women with fibroids experience severe symptoms. These may include abnormal uterine bleeding, iron-deficiency anaemia, infertility, pelvic pain, back pain, and urinary or gastrointestinal issues that need to be addressed [3]. Transvaginal ultrasound imaging is the preferred diagnostic modality for fibroids, while a computed tomography (CT) scan provides a comprehensive visualisation of the underlying cause in most bowel obstruction cases [4]. The available treatment options for symptomatic fibroids encompass expectant management, medical therapy, interventional radiology procedures, and surgical intervention [5]. The primary objective in the management of bowel obstruction is to alleviate the obstruction, which can be achieved through conservative measures such as nasogastric decompression or surgical intervention including adhesiolysis and bowel resection. In cases where the obstruction is caused by uterine fibroids, as in the present case, myomectomy may be performed concurrently with these procedures [4].

Case report

The patient was referred to the General Surgery department, where a general examination revealed a body mass index (BMI) of 26.5, and she was afebrile. The 44-year-old female was nulliparous and expressed the desire to remain childless, she had had lower abdominal pain for three days that had been accompanied by several episodes of vomiting, while her last bowel movement had been 96 hours prior. During physical examination, a palpable, painful abdominal mass was seen in the lower abdomen. A digital rectal examination revealed firm stools with no blood. Complete blood tests done in the emergency department are summarised in Table 1. An X-ray examination was performed in supine view showing signs of small bowel obstruction (SBO) with air fluid levels (Fig. 1). A CT scan of the abdomen was urgently performed. Proximally dilated small bowel loops (ileus and jejunum) were visualised, with a clear transition point located in the right lateral abdomen (adjacent to the lower pole of the right kidney), indicative of mechanical obstruction (Fig. 2). The distal bowel loops, including the large intestine, were collapsed, further confirming a complete obstruction. Additionally, multiple, enlarged, well-defined masses with heterogeneous enhancement, consistent with fibroids, were observed occupying the anatomical location of the uterus. These fibroids were identified as the primary cause of the ileus due to their mass effect on the adjacent bowel structures (Fig. 3). A small amount of free intra-abdominal fluid was present in the lower abdomen, hepatorenal, and splenorenal spaces, possibly secondary to the obstructive process. No other focal abnormalities were detected in the solid organs, nor were pathologically enlarged lymph nodes noted, ruling out neoplastic involvement. All the above suggested a fibroid-induced SBO, an unusual yet clinically significant finding. Given the patient’s worsening abdominal symptoms following admission, a decision was made to proceed with an abdominal hysterectomy. Preoperative counselling was conducted to discuss surgical options, considering the patient’s desire for future sterilisation. The patient was positioned supine and administered general anaesthesia. A midline abdominal incision was made. Intraoperative exploration revealed a markedly dilated loop of jejunum with a palpable mass proximal to the mid-jejunum. Minimal intraperitoneal serous fluid was observed. A hysterectomy was subsequently performed. The excised fibroid measured 17 centimetres in diameter. The patient was discharged from the hospital on the fourth postoperative day without complications. A follow-up visit was scheduled for 20 days after discharge. At the outpatient clinic visit, the patient reported no symptoms, increased appetite, and regular bowel movements.

Fig. 1

X-ray images of the abdomen: supine view, showing signs of bowel obstruction with multiple air-fluid levels

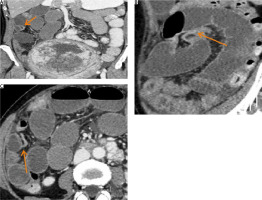

Fig. 2

Abdominal CT scan post-contrast images (A) coro nal view, (B) sagittal view, and (C) transverse view showing the transition zone (orange arrows) in the right lateral abdo men, with proximally dilated SB loops, consistent with SB ob struction due to enlarged fibroids

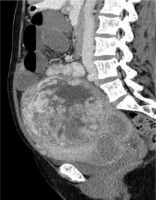

Fig. 3

Sagittal view – post-contrast CT scan showing multiple large, heterogeneousl, enhanced uterine masses and air-fluid levels in the small bowel, suggesting SB obstruction. The enlarged fibroid is observed displacing the bowel loops superiorly and laterally

Table 1

Complete blood tests done in the emergency department

Discussion

Small bowel obstruction, a common surgical emergency, is characterised by the mechanical blockage of the intestinal lumen. While various pathological processes can contribute to this condition, intra-abdominal adhesions represent the primary aetiology in developed regions. Small bowel obstructions can be classified as partial or complete, and further categorised as non-strangulated or strangulated [6]. The incidence of SBO is comparable between males and females. The occurrence of bowel obstruction as a complication of uterine fibroids is infrequently reported in the medical literature, suggesting its relatively rare incidence. However, the risk of this condition increases with age and the number of prior intra-abdominal surgical procedures [7]. In most cases of SBO, an abdominal X-ray taken while lying down shows distended loops of the small bowel and a lack of gas in the large bowel. When X-rays are taken while standing or lying on one side, air-fluid levels in a step-like pattern can be seen. These findings, along with the absence of gas and stool in the lower colon and rectum, strongly indicate mechanical intestinal obstruction [8]. The American College of Radiology recommends using CT as the first imaging method for evaluating intestinal obstruction in patients with a high degree of clinical suspicion. Intravenous contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis is suggested for patients with suspected high-grade obstruction, while oral contrast media may be used for patients without high-grade obstruction or when intravenous contrast is not feasible. Following these guidelines increases the sensitivity of CT in detecting high-grade obstruction and helps in identifying the cause and location of obstruction accurately [9]. Uterine fibroids, a benign neoplasm of smooth muscle tissue in the gynaecological domain, exhibit an increasing incidence, affecting approximately 25% of women of reproductive age. However, only around 25% of these individuals experience symptomatic manifestations [10]. An increased risk of uterine fibroids has been identified in individuals of African descent, those with a positive family history, women older than 40 years of age, nulliparous individuals, and those with obesity [11]. The evaluation of fibroids primarily centres on the patient’s presenting symptoms, which include abnormal menstrual bleeding, bulk symptoms, pelvic pain, or indicators suggestive of anaemia [12]. In some instances, fibroids are discovered in asymptomatic women during routine pelvic examinations or incidentally during imaging procedures [13]. The treatment of uterine fibroids should be individualised based on the size and location of the tumours, the patient’s age, symptoms, desire to maintain fertility, access to available treatments, and the physician’s expertise [14]. Conservative therapy for uterine fibroids centres on hormonal manipulation through the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, GnRH antagonists, oral contraceptives, and progesterone receptor modulators, in conjunction with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tranexamic acid [15]. Surgical therapy for uterine fibroids includes myomectomy, uterine artery embolisation, and, as a final option, hysterectomy.

Hysteroscopic myomectomy is the preferred surgical approach for women with submucosal fibroids who desire to preserve their uterus or fertility. It is most suitable for submucosal fibroids measuring less than 3 centimetres when more than 50% of the tumour protrudes into the uterine cavity [16]. Uterine artery embolisation is a minimally invasive procedure that serves as a compelling option for women seeking to preserve their uterus or avoid surgical intervention due to medical comorbidities or personal preference. By selectively blocking the blood supply to the uterus, this procedure effectively addresses conditions such as fibroids and offers a safe and viable alternative to traditional surgical approaches [14]. Hysterectomy offers a definitive cure for women with symptomatic fibroids who do not desire to preserve fertility, leading to the complete resolution of symptoms and an enhancement of quality of life. The most effective treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroids involves hysterectomy performed through the least invasive approach feasible [17]. When dealing with a uterine fibroid leading to bowel obstruction, it is essential to employ standard procedures such as the use of a nasogastric tube for decompression, maintaining the patient on nil per os (NPO) status, providing hydration, and administering appropriate analgesics [15]. If the patient’s condition does not show improvement with conservative measures, it is crucial to strongly consider surgical intervention. Although tumour markers, such as CA 125 and CA 19-9, can be useful tools that help to distinguish between benign and malignant ovarian masses, their role remains unclear in uterine fibroids causing small bowel obstruction [18–21].

Conclusions

Large uterine fibroids can cause mechanical small intestine obstruction, although this is not a common cause. Diagnostic imaging, particularly computed tomography, plays a crucial role in diagnosing and determining appropriate management plans. Accurate monitoring and imaging can lead to improved patient outcomes by avoiding unnecessary surgical intervention and reducing morbidity and mortality rates. Treatment options include both medical and surgical methods. Both approaches have proven effective, with surgical procedures being the last resort if medical treatments are unsuccessful. The accuracy and efficacy of these surgical methods have shown promising results and significant prognostic benefits.