Introduction

Epidemiology serves as a foundation for all activities carried out in the field of public health in a broad sense. Not only does epidemiological research allow for identifying the incidence of particular diseases along with their aetiology and variability, but it also creates the underlying basis for designing preventive health practices, implementing methods of early detection, improving treatment options, and assessing the financial consequences directly or indirectly related to specific disease entities. Standardized international research projects conducted in accordance with clearly defined guidelines across numerous countries are of particular importance as they enable global evaluation of health problems and comparison of disease incidence in particular regions of the world. This is especially important in the case of allergic diseases, which are predominantly environmental in nature.

Epidemiological research provides us with the ability to discover the natural history of allergies and associated population dynamics as well as determine time trends and implement them to accurately predict factors which may be valuable in planning health care programs for patients suffering from allergic diseases [1–3].

Rapid growth of allergic disease incidence has been observed worldwide, which has been particularly visible among populations of children, adolescents, and young adults in developed countries. This is the reason why allergy has been proclaimed the epidemic of the 21st century. Such trends require us to get involved in a comprehensive global analysis of cause-and-effect relationships in the field of allergic diseases focused on climate zones, environmental factors (exposure to individual allergens and air pollution), civilization progress, and dietary habits [2, 3]. From a global perspective, there are two crucial systems that contributed the most to the epidemiological research on allergies and asthma: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) [4] – a survey of children and adolescents aged 6–7 and 13–14 years, which was conducted in three phases in 56 countries from various regions of the world in the years 1992–2003, and the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) [5] – a study which evaluated the incidence of asthma and allergies in a group of young adults aged between 20 to 44 years of age. The first edition of the ECRHS study carried out in the early 1990s involved 22 countries and was of screening character. The next edition of this research project took place in the second half of the 1990s – it was conducted in 38 European centres and allowed for a more detailed verification of the diagnosis of asthma and allergies. These two studies have significantly expanded our understanding of the causes behind asthma, allergic rhinitis (AR), food allergy (FA), and atopic dermatitis (AD). It is extremely important that these studies implemented questionnaires containing simple questions, therefore allowing for the development of clear diagnostic criteria in allergic diseases which were unified across different countries [4, 5].

Aim

This manuscript presents a study which aimed to assess the accuracy of diagnosing the following allergic diseases: allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis, and food allergy, with the use of modified, validated, and standardized questions from the ISSAC and ECRHS questionnaires.

Material and methods

The study examined a total number of 1,000 respondents from three clinical centres located in central Poland: Warsaw, Lodz, and Poznan. These centres were carefully selected based on their similar topographic properties and environmental conditions. Our research project was divided into two main stages: the first phase involved the use of modified, validated ISSAC and ECRHS questionnaires, while the second phase (conducted in an outpatient setting) focused on making a diagnosis of allergic diseases based on patient answers to questionnaires and results of skin testing and spirometry. The first stage of the examination featured a question which was aimed to diagnose various forms of allergies: Has your child ever experienced problems with sneezing or a runny or blocked nose, when he/she did not have a cold, fever or flu at that time? for allergic rhinitis; Has your child ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest? Has your child had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the last 12 months? for asthma; Has your child ever had eczema (dermatitis) or any other form of skin allergy? for atopic dermatitis; Has a doctor ever diagnosed your child with food allergy? If yes, to what food allergens? for food allergies. The clinical stage of our research involved diagnosing allergic diseases according to the following guidelines: Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) [1] for allergic rhinitis, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) [6] for asthma, Hanifin-Rajka criteria for atopic dermatitis [7]. Food allergy was diagnosed by means of a clinical interview and positive skin tests. All participants had skin diagnostic tests performed (Allergopharma, allergens tested: paper birch, hazel, alder, grasses, rye, mugwort, ribwort plantain, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae, Alternaria tenuis, Cladosporium herbarum, cat and dog hair allergens, histamine and control test) along with spirometry (Lungtest 1000). Skin tests were interpreted based on the wheal size, while spirometry used FEV1/FVC and FEV1 index to evaluate the risk of airway obstruction. Distribution of study groups within individual clinical centres was comparable in terms of age and gender. Positive family history for allergic diseases was mainly observed in the maternal line (Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics of the study group

Statistical analysis

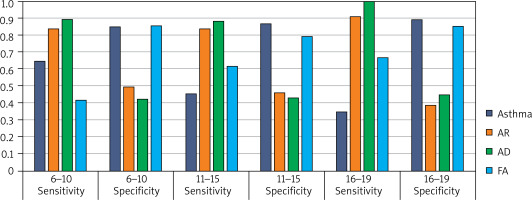

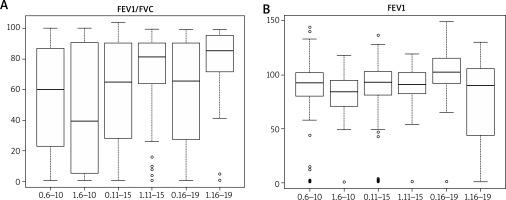

Statistical analysis allowed us to determine the prevalence of particular allergies and create contingency tables for individual allergens for the following diseases: asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and food allergy. Logistic regression estimated the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals, therefore allowing to determine the correlation between AR and other allergic diseases (asthma, AD, and FA). Box plots showing distributions of spirometry parameters were also compared: FEV1 and FEV1/FVC for patients suffering from asthma and healthy individuals. Finally, a medical diagnosis made with the use of questionnaires (containing questions about typical symptoms of a given disease) was verified in terms of its sensitivity and specificity. The questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity in detecting asthma were verified with spirometry, given that 85% of the worst results were classified as a presence of the disease, while the remaining 15% representing the best results assigned our study participants to a healthy group. Additional skin tests for selected allergens specific to a given disease entity were implemented in the process of diagnosing AR, AD, and AP (at least one allergen for +, at least one allergen for ++, and at least one allergen for +++). In order to confirm the diagnosis, a patient is required to present symptoms of an appropriate disease entity based on the answers in a questionnaire, along with positive skin test results for at least one allergen (+, ++, +++) or spirometry results in case of asthma as compared to a group of healthy individuals (those without a questionnaire-based diagnosis and normal skin test and spirometry results).

Significant differences in the incidence of allergic diseases were observed between particular age groups (6–10 years, 11–15 years, 16–19 years) within the three analyzed clinical centres (Warsaw, Poznan, Lodz).

Results

Based on the responses provided in questionnaires, the presence of AR was identified in almost half of the examined population of 6–10-year-old children, in approximately 40% of children aged 11–15 years, and in around 15% of respondents aged 16–19 years old (Table 2). Asthma symptoms were reported by over 50% of respondents from the youngest age group, by every third person in the 11–15 age group, and nearly 11% of study participants from the oldest group. The outpatient phase of the study provided the following results: the highest numbers of confirmed AR cases was reported in the group of 11–15-year-olds and 16–19-year-olds, while the smallest number of confirmed diagnoses was noted in the youngest group of participants. Asthma was diagnosed predominantly in the 11–15 and 16–19 age groups. AD most often affected participants aged 11–15 years, while FA was most frequently seen in the youngest patients and reached 7% of all examined individuals. In the analysis of the risk of allergic comorbidities, only AR was found to increase the risk of coexisting asthma among respondents who belong to the youngest age group and those aged 11–15 years (asthma was diagnosed over two times more often in these individuals).

Table 2

Questionnaire-based diagnosis (e-allergy) compared to clinical examination (conducted in an outpatient setting)

Positive response in skin testing of patients diagnosed with AR was most often observed to the following allergens: rye, grass, dust mites, cat hair, ribwort plantain, and Alternaria tenuis (Table 3). The most significant allergic reaction in skin prick tests was reported in individuals who were allergic to grass pollen, grains, and dust mites. People with asthma were most commonly allergic to grass/hazel, rye, dust mites, and cat hair allergens. The highest skin sensitivity to the administered allergens was reported for the following allergens: grass, dust mites, rye, and hazel. In patients diagnosed with AD, milk was much more likely to trigger an allergic reaction as compared to all other tested allergens. In a group of patients with FA, eggs demonstrated the highest allergenic potential. The FEV1/FVC ratio remained relatively diverse among the study groups – It was 50.32% (median 39.50) in a group of 6–10-year-olds, 69.53% (median: 81.45) among 11–15-year-olds and 74.25 (median: 85.40) in the oldest patients aged 16–19 years. Similarly, the FEV1 index illustrating the degree of bronchial tree obstruction was found to differ significantly between individual study groups: it was 80.50% (median: 84.50) among 6–10-year-old children, 84.74 (median 90.85) in a group of patients aged 11–15 years and 75.01 (median: 90.00) among individuals aged 16–19 years (Figure 1).

Table 3

Positive skin prick testing in the study group

Figure 1

Parameters characterizing the functioning of the lower respiratory tract obtained in spirometry (in age groups 6–10, 11–15, 16–19, 1 – with asthma, 0 – without asthma)

Specificity and sensitivity of modified questionnaires

The specificity and sensitivity of modified questionnaires (implemented in the first stage of our study) varied between particular study groups depending on the type of allergic disease diagnosed and age. Among participants aged 6–10 years, the specificity and sensitivity were: AR 0.84 and 0.50, asthma 0.64 and 0.85, AD 0.90 and 0.42, FA 0.42 and 0.85, respectively. Values reported in the group of 11–15-year-olds: AR 0.83 and 0.46, asthma 0.45 and 0.87, AD 0.89 and 0.43, FA 0.61 and 0.80. Finally, respondents aged 16–19 years demonstrated the following values of specificity and sensitivity of modified questionnaires in diagnosing allergic diseases: AR 0.91 and 0.39, asthma 0.35 and 0.89, AD 1.0 and 0.45, AP 0.67 and 0.85 (Figure 2). The second stage of our study was aimed to verify the effectiveness of diagnosing allergic diseases with questionnaires by performing skin testing and spirometry examinations. High accuracy of a questionnaire-based diagnosis of allergic disease was observed primarily in AR and asthma (Table 4).

Table 4

Specificity and sensitivity of tests used to diagnose allergic diseases vs. E-allergy diagnosis (skin prick testing)

Discussion

Our study implemented modified ISSAC and ECRHS questionnaires in order to determine the incidence of allergic diseases in paediatric populations in three regions of Poland. The effectiveness of these surveys involved comparing their specificity and sensitivity based on the results of clinical examination (conducted in an outpatient setting) with the use of validated test methods such as spirometry, skin prick tests, physical examination, and medical interview. Our study may serve as a continuation of the ECAP study (Epidemiology of Allergic Diseases in Poland) conducted in the years 2006–2009 [8]. The ECAP research used full versions of ECRHS II and ISAAC questionnaires which were translated and validated in a pilot study. A total number of 22,703 respondents from 9 clinical centres in Poland were examined in the ECAP project. Participants were assigned to three age groups: children aged 6–7, children aged 13–14, and adults aged 20–44. ECAP reported the average incidence of allergic rhinitis as 23.6% in the youngest group, 24.6% among 13–14-year-olds, and 21.0% for adult patients. To compare, the frequency of AR diagnosed during clinical examination was 28.9% (determined for a group of 4,873 respondents who account for 25% of all tested by ECAP questionnaire). Declared asthma (that is, diagnosed only by questionnaire) was reported in 4.4% of children aged 6–7, in 6.2% of children aged 13–14, and in 4% of adults. The frequency of asthma diagnoses confirmed clinically was even higher, reaching 11.4% in both groups of children and 9.5% in a group of adult participants. The conclusions from comparing the incidence of declared asthma cases (diagnosed by the questionnaire) with asthma cases diagnosed by means of medical examination are very interesting. It turned out that the majority of patients (up to 80%) were not aware of their disease [8–11]. The idea of an epidemiological research program focused on the prevalence of allergic diseases in children was first put forward in 1991 as a response to an alarming increase in the incidence of allergic diseases in this population. The years 1993-1997 brought the first stage of the ISSAC study, which included 700,000 children from 56 countries, classified into two age groups: 6–7 years old and 13–14 years old. The study demonstrated that the incidence of allergic diseases varies among different regions of the world. To illustrate this phenomenon, the average prevalence of AR in the population of children aged 13–14 was 7.5% but it could range from 1.4% of affected children in Albania to even 39.7% in Portugal. The results of this study led to further attempts to evaluate the impact of economic and geographical factors, dietary habits, infection-related factors, and exposure to allergens, on the incidence of allergic diseases. Moreover, it turned out that the incidence of allergic diseases in children aged 13–14 years varies even as much as 20-fold between some of the 155 centres participating in the first stage of the study [12, 13]. The second stage of the ISSAC study was focused on identifying factors which contribute to such differences and this phase involved 30 research centres from 22 countries. Not only did this study implement validated questionnaires, but it also used research protocols for AR, asthma, and atopic dermatitis, as well as skin prick testing (SPT), allergen provocation tests with hypertonic saline solution, measurement of IgE level and analysis of house dust samples [12, 14]. The third stage of ISSAC was conducted 5 years after the first one and its results were reported in 2006. Stage III included 1,059,053 children from 236 centres in 98 countries around the world. Increased frequency of reporting allergic disease symptoms was observed in numerous research centres evaluated in previous stages of the study. However, no increase was reported in those clinical centres which initially demonstrated a high incidence of allergies among older children. Stage III of ISSAC project used only questionnaires and no clinical examinations (in an outpatient setting) were conducted [15].

It is worth emphasizing that the ISSAC questionnaires, in their full or modified forms, were later implemented for numerous research projects in the field of allergic diseases epidemiology, thanks to their comprehensive character combined with questions which were easy to understand and interpret. Wijs et al. conducted a study (The Growing Up Healthy Study (GUHS)) in which they compared the incidence of asthma and allergies between a group of children conceived with the use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and naturally conceived children. The methodology of their study was based on the use of ISSAC and SPT questionnaires, methacholine challenge test, and spirometry. Although no differences were observed in terms of asthma or atopic dermatitis incidence between both groups, bronchial hyperresponsiveness was less frequently reported among children conceived with the use of ART techniques. This group was also characterized by a higher incidence of AR and FA [16]. Another study conducted by Kurosaka et al., which aimed to evaluate the incidence and risk factors for wheezing, skin allergy, and rhinoconjunctivitis in a population of Japanese children, featured the use of a modified ISSAC questionnaire. This research has shown that the presence of food allergy combined with a family history of allergic diseases has a significant impact on the development of wheezing, skin allergy, and allergic rhinitis in a group of 6-year-olds. On the other hand, attending nursery in the first 2 years of life and having older siblings was found to decrease the risk of developing allergy [17]. A study conducted on a group of Korean children by Kim et al. focused on assessing the incidence of AR and determining the accuracy of ISSAC questionnaires in diagnosing allergies. A total number of 425 children were included in the study and the researchers decided to implement questionnaires and SPT in their work, while also verifying the presence of comorbid allergic diseases (asthma, atopic dermatitis, food allergy). The questionnaire’s effectiveness in making a correct diagnosis was estimated at 60% and we know that this number is higher than the real number of Korean children suffering from AR [18]. Similar observations were made in the course of our study. Swiss research has demonstrated that, although the ISSAC questionnaires are very detailed and may be a valuable tool in diagnosing allergies due to their high predictive value in children presenting symptoms, these questionnaires prove less effective in detecting allergies in a general population, that is, the ISSAC questionnaires are characterized by lower sensitivity (42.7 %) and higher specificity (77.5%) [19].

The ISAAC study identified significant, up to 15-fold, differences in the incidence of asthma (diagnosed based on the presence of wheezing) between individual centres. In the group of 6–7-year-old children, asthma symptoms were most often reported in Costa Rica (37.6%), Brazil (24.4%) and New Zealand (22.2%). Out of European countries, the greatest number of cases was seen in Great Britain (20.9%). Symptoms of asthma were the least commonly reported in Indonesia (2.8%) and Albania (5.0%). In the group of older children aged 13–14 years, asthma symptoms were found to be most common in Ireland (26.7%) and the USA (22.3%), and least common in Albania (3.4%), Georgia (5.1%) and Indonesia (5.2%). ECRHS is another large asthma-related study which included the examination of patients between 20 and 44 years of age and was conducted in 48 centres from 22 different countries. This study also confirmed findings reported in previous research projects in this field – there are significant geographical differences in the incidence of allergic diseases. According to the results of ECRHS, asthma was least commonly seen in Estonia (2%) and Greece (2%), while it was most often diagnosed in Great Britain (8.4%) [5, 20]. The ECRHS questionnaire serves as a highly useful diagnostic tool for assessing the incidence of asthma and is often implemented in research. AlShareef was the first to use the Arabic version of the ECRHS questionnaire in his study conducted in Saudi Arabia, proving its high sensitivity [21]. Out of 2,500 people invited to take part in our study, 1,881 (75.2%) decided to participate. Out of 1,881 respondents, 668 (35.5%) reported the presence of respiratory symptoms, and 157 (8.3%) individuals had previously been diagnosed with asthma. Ultimately, 543 (81.3%) patients underwent medical examination with spirometry, leaving 278 (52%) participants with a diagnosis of asthma, made in accordance with the GINA guidelines. We managed to confirm the high specificity and varying sensitivity of questionnaire-based testing in diagnosing asthma and therefore proved the usefulness of this relatively simple tool. The overall prevalence of asthma determined in our study population was 14.8%.