Introduction

One of the most common difficulties in older adults is cognitive impairment, which develops gradually. Physical activity [1], smoking [2], and eating habits are some of the factors influencing the development of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Furthermore, such disorders as diabetes mellitus [3] and hypertension [4], which are more common in older women [1, 5], have been linked to the severity of MCI. Aging brings about a variety of physiological and anatomical changes.

Mild cognitive impairment development is linked to neurodegenerative illnesses, a reduction in brain cerebrovascular oxygenation, and a change in glucose metabolism as people get older [6]. In older adults, atherosclerosis and inflammatory processes play a role in metabolic dysfunction [7]. Also, in neuronal populations, mitochondrial dysfunction impacts energy generation and oxidative capacity. As a result, aging reduces the production of adenosine triphosphate and oxidative phosphorylation [8]. According to studies, brain toxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction can cause neurodegenerative disorders and MCI progression [9, 10].

Transcranial photobiomodulation (tPBM) is a recently discovered neuro-interventional technique. In this technique, the light in red and near-infrared spectrums is emitted, which can penetrate the underlying cortical regions of the scalp [11]. By modulating mitochondrial function and enhancing regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF), the tPBM targets the biological function of brain tissue while maintaining its physiological benefits. It also produces antioxidants and anti-apoptotic molecules, which protect the cells from harm [12, 13]. As a result, light therapy has been recognized as a viable treatment option for underlying age-related biological alterations. Regarding the positive effects of tPBM in age-related cognitive and clinical disorders, studies show that it could improve frontal cognitive performance in healthy older adults; in addition, it increases CBF and improves executive function [14–18].

One of the essential cognitive capacities compromised during age-related MCI is attentional function [19]. The individuals’ daily tasks, such as driving, are hampered by a lack of attentional performance, which impairs physical and mental function, as well as postural balance [20]. Mild cognitive impairment and attentional performance disruption are more common in older females [21, 22], so they have slower reaction times and make repeated errors when doing psychomotor attentional tasks [23]. Females may be more susceptible to inattentive signs and their consequences [24]. According to the evidence, in both young and senior age groups, female gender is connected with all parameters of low sustained attention and cognitive processing speed [25]. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the effect of multi-session tPBM on cognitive capacities and attentional function of older women with MCI.

Material and methods

Participants and procedure

This single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted on 42 elderly women with MCI in Tabriz, Iran from September to December 2020. The patients were randomly assigned into two equal groups of real (tPBM) and sham. Using the random block approach, the participants were recruited from the older women referred to the centres providing health facilities to older people. Random allocation software was used to generate the random sequence [26]. Other demographic information, including age, education, daily physical activity, psychological and cognitive status, and history of diseases, was obtained from the medical charts of the patients.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: women over 60 years old with little cognitive impairment, normal or corrected vision, and without use of hearing aids. The exclusion criteria were as follows: history of severe cardiovascular, neurological, or psychological problems, communication impairments, and neuromuscular pain or disability, particularly in the trunk and upper extremities. Also, participants who did not finish their experimental process were excluded from the study.

Manipulation procedure

The research was carried out in 3 stages as follows:

stage 1 (pre-interventional cognitive assessment): in this stage, we employed the MMSE and the Go/No-Go attentional test to measure the severity of cognitive impairment and attentional status, respectively,

stage 2 (intervention): in this stage, the tPBM intervention was performed,

stage 3 (post-intervention): in this stage, we re-evaluated the cognitive status and attentional performance (Fig. 1).

Stage 1: pre-intervention

Evaluation of the cognitive impairment

The mini-mental state examination cognitive test was used to assess the cognitive status. The total score range for the MMSE test is 0–30 [27]. Foroughan et al. (2008) tested and confirmed the validity and reliability of the MMSE test, with specificity and sensitivity of 84% and 90%, respectively. A mini-mental state examination score of less than 21 indicated cognitive impairment [28].

Assessment of attentional status

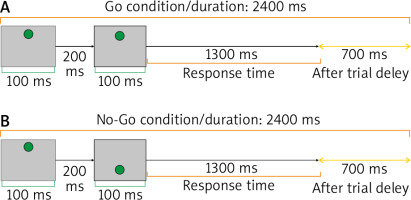

In this investigation, the psychomotor Go/No-Go attentional task was utilized to assess the effect of tPBM on the right frontal pole of the brain. This region is in charge of maintaining attention [29]. The Go/No-Go task is a complicated psycho-behavioural technique in which 2 distinct Go and No-Go conditions are presented. The subject was required to answer as rapidly and precisely as possible to a prepared Go stimulus when it appeared on the screen. It was explained that the participants should not respond to the stimuli in No-Go scenarios. The Go condition appeared in 80% of trials, while the No-Go condition appeared in 20%. For the task presentation in this investigation, we employed Psytask software (Mitsar, Moscow, Russia). The Go/No-Go assignment was used for 10 minutes, with a total of 250 criteria completed. Each Go and No-Go condition lasted 2400 milliseconds, with 100-millisecond stimulus and 200-millisecond inter-stimulus periods. Figure 2 depicts the features of the task [30].

Fig. 2

Go/No-Go task. A) Go condition: sequential presentation of two large grey squares containing a small green circle in the upper part of the screen [Up (200, 100), Up (1300, 100)] with 700 ms after trial interval, B) No-Go condition: sequential presentation of two large grey squares containing 2 small green circles. In the first presentation, the small green circle was at the top and the second circle was presented at the bottom [Up (200, 100), Bottom (1300, 100)], with 700 ms after trial interval

The participants were requested to sit in a chair with their backs to the screen (15 inch) panel at a distance of 70 cm. They were instructed to hit the reply button (computer-connected microswitch) with their index finger as rapidly as possible to answer to the target. All participants rehearsed the task for 2 minutes before beginning the experiment, to become familiar with the method. They were then instructed to respond to the Go stimulus as soon as it appeared and to ignore the No-Go trials.

The following variables could be learned through using the Go/No-Go task:

the reaction time to the target (RTT): this metric is used to determine the average response time for correct responses,

percentage of correct trials (PCT): this variable is calculated by dividing the number of correct responses by the total number of potential answers for each task level,

attentional performance assessment by calculating an efficiency score (ES) using the following equation: ES = (PCT/RTT) × 100.

According to the algorithm, this variable balances the response accuracy and response time, implying that people who answer more often correctly and faster have a higher ES value. Furthermore, individuals with lower ES values were those who replied faster and more accurately, or responded faster and less accurately. Individuals who processed the information with less speed and precision obtained the lowest score.

Stage 2 (intervention)

In this study, tPBM was used for 5 daily sessions (in compliance with Circadian Rhythms 9–12 a.m.). We used an 850-nm multi-array LED device (20 NIR LEDs, total power: 400 mW, power density: 285 mW/cm2, energy density: 42.75 J/cm2, total dose delivered to the scalp: 60 J [400 mw 2.5 min], area of irradiation: 1.4 cm2, peak wavelength: 850 nm, max: 870 nm, spectral bandwidth: 30 nm, spectral bandwidth: 30). The Lumix3 calibrator was used to calibrate the device’s output power (Lumix3, Italy). The forehead region was irradiated in a 4 cm2 area. The beam source was 2 cm2 away from the target forehead area. According to the usual EEG 10–20 technique, light was irradiated on the right frontal pole of the cortex (FP2) for 10 minutes [31, 32]. This part of the brain is in charge of higher-order cognitive functions like alertness and attention. The real group received tPBM for 10 minutes in 5 sessions. Each minute, the sham group was only exposed to a small amount of light for 30 seconds.

Stage 3 (post-intervention)

To assess the effect of the tPBM, cognitive impairment and the attentional Go/No-Go task were used again after the intervention. The workflow is depicted in Figure 3.

Ethical considerations

This randomized controlled trial was registered at the Iranian clinical trials registry (IRCT20171031037124N2). In addition, the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (IR.TBZMED.REC.1398.1054). The participants were free to leave the study at any time.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilks test was used to assess the normality of data. Before the intervention, the 2 groups were compared using an independent t-test. To check the changes before and after the intervention, a paired t-test was performed. In the presence of covariate variables, such as education (primary, secondary, university), marital status (married, single), physical activity (less than 30 minutes), age, and body mass index (BMI), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed to check if the ES (PCT/RTT) and MMSE improved after the intervention. To do so, the following settings were used after the intervention, the ES (PCT/RTT) levels and MMSE were considered and the educational level, marital status, physical activity, age, and BMI were considered as variables.

A t-test with a significance level of 0.05 was used for post-hoc analysis. SPSS 25 was used for statistical analysis (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the results of the demographic variables in the 2 groups. At baseline, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of age, BMI, marital status, physical activity, and education. Table 1 shows the results of the χ2 and independent-samples t-tests used to compare the levels of qualitative and quantitative demographic factors.

Table 1

General characteristics of participants in both groups

Cognitive status

Prior to the intervention, there was no significant difference in the mean total MMSE score between the real and sham groups (p = 0.54). Also, according to the results of ANCOVA, none of the confounding variables had a significant effect on the MMSE score. There was a significant interaction between group × time F (1, 40) = 20, p < 0.001, h2 = 0.33). According to the results of post-hoc paired-samples t-test, the mean MMSE significantly increased in the real group (t = 15.9; p = 0.001; d = 9.3) but did not change significantly in the sham group (t = 0.7; p = 0.81, d = 0.3). Furthermore, the partial Eta coefficient indicated that intervention was responsible for 33% of the variable changes in response (Fig. 4).

Attentional performance

Reaction time to the target

Before the intervention, there was no significant difference in the mean total RTT score between the real and sham groups (p = 0.30). The results of the ANCOVA on the RTT score revealed that none of the confounding variables had a significant effect on the RTT score. The findings revealed a substantial interaction between group × time F (1, 40) = 17, p < 0.001, h2 = 0.38). The results of paired-samples t-test revealed that while the mean RTT significantly decreased in the real group (t = 4.8; p = 0.001; d = –37.4), it did not change significantly in the sham group (p = 0.7). In other words, the intervention was successful in reducing the average RTT. Furthermore, according to the partial Eta coefficient, 38% of the variables changed in the study (Fig. 5).

Percentage of correct trials

There was no significant difference in the mean total PCT score between the real and sham groups before the intervention (p = 0.24). The results of the ANCOVA on PCT score revealed that none of the confounding variables had a significant effect.

Also, the findings revealed a significant relationship between group × time F (1, 40) = 13, p < 0.001, h2 = 0.31). According to the results of paired-samples t-test, while the mean PCT significantly increased in the real group (t = 2.67; p = 0.015; d = 6.3), it did not change significantly in the sham group (p = 0.59). In other words, the intervention was successful in increasing the average PCT. Furthermore, according to the partial Eta coefficient, the intervention changed 31% of the variables (Fig. 6).

Efficiency score

Before the intervention, there was no significant difference in the mean overall ES between the real and sham groups (p = 0.14). The results of the ANCOVA on the ES score revealed that none of the confounding variables had a significant effect.

The findings revealed a significant association between group × time interaction F (1, 40) = 19, p < 0.001, h2 = 0.32). According to the results of paired-samples t-test, while the real group had a significant increase in the mean ES t = 5.3, p < 0.001, d = 0.034), the sham group had no significant change in this regard (p = 0.33). In other words, the intervention significantly increased the average ES. Furthermore, according to the partial Eta coefficient, the intervention changed 32% of the variables (Fig. 7).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of tPBM on cognitive function and attentional performance in older women with MCI. The findings showed that 5 sessions of tPBM over the right prefrontal cortex (rPFC) improved cognitive capacities and attentional performance in elderly women.

The cognitive function was tested using an MMSE questionnaire. The results showed that after 5 sessions of tPBM, the cognitive score improved, which was consistent with previous studies reporting that tPBM was useful in enhancing cognitive functioning in healthy elderly adults and in clinical situations [15]. Research has shown that tPBM can improve cognitive function in individuals with neurodegenerative diseases such Alzheimer’s disease [33], dementia, Parkinson’s disease [34], and chronic traumatic brain injury [35]. According to Chan et al. (2019), cognitive performance and mental plasticity increased in healthy older adults following a single session with 870-nm tPBM [14]. These studies highlighted memory improvement [36], attention retention [17], and executive functioning [14, 17]. Furthermore, according to the evidence, tPBM improved dementia patients’ behaviour and cognitive performance, as well as insomnia [37], anxiety, and violent behaviours [38].

This study also demonstrated that the intervention significantly decreased the reaction time, which was consistent with the studies [39, 40], reporting that cognitive abilities significantly improved in participants receiving the treatment. In their study, individuals who underwent tPBM had a faster reaction time (measured by the psychomotor vigilance test). According to another study by Chan et al., tPBM improved the cognitive function of the elderly people, and only the mean reaction time significantly changed in the experimental group [14].

In our study, the PCT was also improved. The improved attention and motor skills in response to the proper stimulus are indicated by a higher PCT score. As this score rises, the performance of the irradiated area in controlling the inhibition of response to the requested task may improve; this has been supported in some previous research [39, 40]. In the study by Holmes et al. [41], psychomotor performance improved and patients showed faster reaction times and a higher number of accurate experiments after tPBM treatment.

In our study, 5 sessions of tPBM in the real group improved ES through enhancing attentional performance on the Go/No-Go task. The ES was estimated by combining the individual’s reaction time to target trials with their ability to avoid reacting to non-target conditions. Since the ES improved after tPBM, it was assumed that this modality could be a good candidate for improving psychomotor and cognitive function in older women [39, 40]. The effect of tPBM on the PFC appears to activate the neuronal population and improve the individual’s behaviour. In Go trials, this modality increased performance by speeding up the motor RTT and relaying the PFC’s inhibitory role in preventing non-target responses [39, 40]. Similar previous studies have demonstrated that tPBM improves cognitive and motor skills. In healthy young adults, the right PFC tPBM has been shown to improve memory and attention [40, 42]. In the study by Fekri et al. (2019), motor performance improved following tPBM [43]. Some electroencephalographic studies have reported changes in absolute power and functional connectivity of the brain. The results of these investigations have been interpreted in favour of the tPBM’s positive effects on brain electrical activity [39, 44]. Previous studies have indicated changes in executive performance, such as lock drawing, instantaneous recall, praxis memory, visual attention, and task switching (trials A&B), as well as improvements in EEG electrical patterns. Near-infrared light has also been shown to improve a variety of cognitive abilities, including learning and memory [36], continuous attention [14] and executive functions [17], by regulating mitochondrial function [45], improving CBF [12], and decreasing bioenergetics functions of neural populations [46].

The neuroinflammatory response [47, 48] and modulation of transcription factors in the intervention group may also play a role in the improvement of cognitive capacities following 5 sessions of tPBM. These effects were identified in previous studies after using the tPBM for a long time [49].

In this study, the sham group showed no significant change in cognitive ability or attentional performance. Hence, the favourable effects of tPBM on brain functioning can improve the cognitive skills in the tPBM group.

Conclusions

The current study indicated a beneficial effect of light treatment by using 5 sessions of tPBM on the rPFC with an 850-nm LED source, which consequently improved the cognitive capacity and attentional performance of older women with MCI. The benefits of a 5-session light treatment could be attributed to its immediate and long-term effects on brain tissue, which could be suggested to professionals in the field of geriatrics and neurology to improve cognitive capacity during older age.