INTRODUCTION

Sexuality is defined by the World Health Organization as “(…) a central aspect of being human throughout life, which encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction” [1]. The essential elements of sexual health are, among others, the following: the possibility of achieving sexual satisfaction, freedom from illnesses and ailments, as well as undisturbed sexual development [2].

The psychophysiological process of sexual response in both healthy men and men with the disorder is usually described in relation to the linear model of sexual response. This assumes the existence of the following phases: desire, arousal, plateau, orgasm and resolution. This concept is a modification [3, 4] of the classical model of the physiological sexual response developed by Masters and Johnson [5]. Kratochvil’s Sexual Function of Man questionnaire (SFM/K) [6, 7] was designed according to these assumptions.

Dysfunctions related to sexual expression can have their basis in hormonal imbalance, anatomical structure [8], neurological dysfunctions [9], internalisation of inadequate social attitudes and expectations about male sexual performance, or cultural requirements regarding gender roles [10]. Psychological and psychiatric factors also play an important role [11, 12], as well as difficult life events, which contribute to the emergence of various mental disorders [13, 14]. Sexual dysfunctions are recognised as common symptoms which accompany mental problems. Sometimes their occurrence precedes symptoms of mental disorders [15]. However, the direction of causality seems unclear because sexual dysfunctions and affective disorders are usually tightly linked [12]. It is noteworthy that experiencing stigma, social rejection, and even aggression due to the burden of a diagnosis of mental disorder can cause additional stress affecting general well-being and the quality of sexual performance [11]. According to reports, the most common sexual dysfunctions among men are erectile dysfunction (approx. 10-20%), premature ejaculation (which affects up to 40% of men aged 18-59 worldwide [18]), delayed ejaculation, lack of ejaculation and retrograde ejaculation [17]. Less frequently, men complain about abnormal orgasms (e.g. painful ejaculation) and non-specific pain experienced after intercourse [20].

Sexual dysfunctions are common side effects of antidepressants, especially popular selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI). One of the main mechanisms of drug-induced sexual dysfunction is the agonistic activity towards serotonin 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 [12], resulting in reduced sexual desire, inhibition of orgasm/ejaculation and, sometimes, erectile dysfunction [21].

This study attempted to outline the picture of the sexual functions of Polish male patients suffering from affective disorders, taking into consideration demographic and clinical variables.

METHODS

The study was conducted on a group of patients diagnosed with affective disorders who were under psychiatric care. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice.

The study included 57 men diagnosed with F31 – bipolar disorder type I or II (52.6%); F32 – a depressive episode (5.3%); F33 – recurrent depressive disorder (35.1%); and F34 – cyclothymic disorder (7%). The participants were required to be in remission, so to exclude any distorting effects on sexual expression typical for depressive/dysthymic or (hypo)maniac episodes.

Data on education, residence, diagnosis of affective disorder, duration of the treatment, history of hospitalisation and medication were obtained during interviews conducted by a medical doctor and extracted from the patient’s medical records. This was followed by the use of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) [22] and the Young Mania Scale (YMRS) [23] to evaluate the clinical status of the patients. This procedure allows for the exclusion of the impact of the depressive or maniacal symptoms on patients’ self-description in the Sexual Function of Man according to Kratochvil (SFM/K) questionnaire. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [24] was also used to assess alcohol misuse. Then the participants filled in the SFM/K, which is based on the concept of linear sexual response (the DEOR model in the version for men) and was designed in such a way as to support the detection of sexual problems or dysfunctions in the particular phases of the sexual response [6, 7].

RESULTS

The participants were aged 23 through 61, with a mean age of 47.2 ± 9.5 (median = 49). Most of them (66.7%) lived in cities with over 0.5 million residents, and only 5.3% lived in villages. In this group 14% had a vocational education, 26.3% had a secondary one, and 59.6% graduated from a higher school. The duration of their mood disorder equalled an average 10.9 ± 8.5 years (median = 8), and the mean number of hospitalisations prior to the study was 3.6 ± 5.2 (median = 2). Every participant was in remission and had no severe depressive or maniacal symptoms, as confirmed by the MADRS and YMRS tests.

At the time of the assessment, most patients were being treated with antidepressants (70.2%). Moreover, 28.1% were taking typical neuroleptics and 22.8% atypical neuroleptics, while 7% were prescribed anxiolytics and 14% hypnotics.

The results of the AUDIT questionnaire showed that two subjects (3.2% of the sample) manifested symptoms of “harmful drinking”, and ten of them (16.1%) “risky drinking”, while the remaining 80.4% were in the so-called “no risk” group. None of the patients met the criteria for diagnosis of alcohol addiction.

According to the data gathered from the SFM/K, 75.4% of the respondents see themselves as either constantly (19.3%) or generally sexually effective. However, about 68.4% reported at least one instance of an occurrence of some sexual dysfunction. Their responses indicated ejaculatory dysfunctions (i.e. premature ejaculation) as more common than erectile dysfunction, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (W = 491.5, p = 0.074).

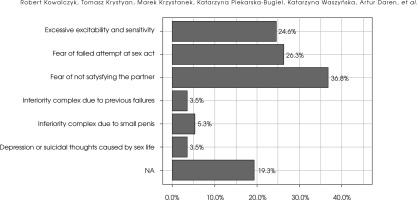

The answers given by the majority of the patients indicate that their partners reach orgasm during sexual intercourse “mostly” (49.1%) or “always under normal circumstances” (26.3%). However, 19.3% indicated that it happens rarely. The partners strongly react to the stimulation of the external genitalia, especially the clitoris (70.2%), rather than inside the vagina (1 person did not answer). Intercourse was more often initiated by males (52.6%) or both partners equally (33.3%) than by women. The most common method of controlling the timing of ejaculation (26.3%) was stopping further body movements before the excitement became too intense. The most frequent and noticeable psychological problem related to the male sexual life was anxiety about not giving sexual satisfaction to the partner (36.8%). At the same time, the least common difficulties were severe mood disorders or inferiority complexes regarding participants’ sexual effectiveness or their own sexual anatomy (Figure I).

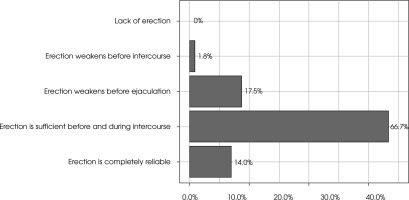

All in all, the quality of erection was reported as sufficient to carry out coitus successfully by two-thirds of the subjects (Figure II).

According to the respondents, who could indicate more than one option (two subjects did not indicate any), the most frequent methods of contraception practiced in their relationships were condoms (49.1%), while methods aimed for women (which included hormonal tablets and vaginal rings) (17.5%) were used less often. A relatively high percentage of responses indicated solutions that do not effectively protect against unwanted pregnancy (i.e. coitus interruptus 31.6%, or sexual abstinence on fertile days 28.1%). For most respondents (93.1%), memories associated with the commencement of sexual life were related to positive or very positive affect.

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis showed that there was a negative link between the age of the onset of a mood disorder and the desire for frequent sexual intercourse (r = –0.29, p = 0.03), as well as the reported frequency of attempted sexual intercourse (r = –0.37, p = 0.005) and how often it was completed (r = –0.29, p = 0.031). Similarly, the age of the subjects was negatively correlated with the desire for frequent intercourse (r = –0.36, p = 0.006), how often it was attempted (r = –0.39, p = 0.003) and the quality of erection (r = –0.3, p = 0.023). Correlations also indicated negative relationships between the duration of affective disorders and the frequency of orgasm experienced by the partner during sexual intercourse (r = –0.28, p = 0.033) and the duration of intercourse (r = –0.4, p = 0.002).

When comparing patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder and those with recurrent depressive disorder, a significant difference in responses was observed regarding mood after sexual intercourse. Higher scores were indicated by patients with bipolar disorder (W = 395, p = 0.028). That is, they reported being in a better mood after coitus. Also, a notable yet statistically insignificant difference was found for a higher reported frequency of attempted sexual intercourse by those diagnosed with bipolar disorder (W = 380.5, p = 0.090).

DISCUSSION

Based on the results obtained in the SFM/K, a small number of differences in sexual functioning among patients with a diagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder and BD have been discovered at the level of statistical significance, or at least the statistical trend. This study’s results show more problematic sexual functioning among patients diagnosed with recurrent depressive disorder. However, there were more similarities than differences between the F31 and F33 groups of male patients.

The general results gained by all patients in the SFM/K were relatively higher than initially expected due to statistics on sexual dysfunctions according to patients’ age and health [26, 27]. Such a finding was caused by recruiting patients in a period of remission. It can also be hypothesised that more mature men, as they were more numerous in our sample, can be more reconciled with the sexual limitations associated with the illness and treatment. It is probable that older patients present a higher level of self-acceptance and sexual adjustment, in comparison to younger ones.

Those respondents with a longer history of illness or diagnosed with recurrent depressive disorder were found to have more impaired sexual functions. Hospitalised patients more often attain lower total scores in the SFM/K. This suggests that a more severe depth and/or persistence of affective disorders accompanies more dysfunctional sexual performance. This hypothesis, however, should be tested in a larger sample.

It can be assumed that sexual dysfunction among men may be affected by a) even the smallest depressive and manic-depressive component; b) some other implicit factor, which is not subject to psychiatric medication; and c) older age.

The self-descriptive SFM/K questionnaire proved to be a helpful tool supporting the sexological interview for men suffering from affective disorders. Nevertheless, the possibility of bias should be noted as a result of distortions, projections and other mechanisms which make patients try to show themselves in a better light when they fill in a sexological questionnaire.

It should be noted that Kratochvíl’s tool – in the versions for both men (SFM/K) and women (SFK/K) – is not a standardised psychometric questionnaire but an adjunct to the sexological interview method. The results obtained are considered mainly in terms of the frequency of specific responses. The results are only indicative, not translated into strict diagnostic indications. In addition, Kratochvíl’s questionnaire is intended to be used in a heteronormative context and its attendant response pattern. Thus it does not offer the possibility of a declaration of sexual orientation or gender identity on the part of respondents. Therefore, it is not very useful for the assessment of homosexual and bisexual men. This can result in potential inconsistencies in the results (i.e. by interpreting gay or MSM as heterosexual).

CONCLUSIONS

As this paper shows, patients with depression seem to have slightly more problems than those with BD in some areas of their sexual functioning. Still, both groups show many similarities in the current study. Furthermore, patients with longer illness histories or with recurrent depressive disorder diagnoses declare more problems in their sexual functioning.

The study has also some limitations. Many confounding variables potentially affect its results. Also, the complexity of the factors relations model makes the direction of causality imprecise. This research can indicate a direction of further scientific research on the topic; however, using the self-description questionnaire is not as precise as standardised psychometric procedures.

Considering the above indications, deepening the analysis with a much bigger sample and a wider variety of affective disorders is recommended.