Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) has 4 major components: ventricular septal defect (VSD), overriding aorta, pulmonary stenosis, and right ventricular hypertrophy [1]. TOF has a favorable long-term outcome with surgical repair [2–4].

The patient – male, 26 years old – had undergone a TOF repair at the age of 2 years. He underwent surgery to replace the pulmonary valve with a 25 mm bioprosthetic valve due to the progression of severe pulmonary insufficiency at the age of 12 years.

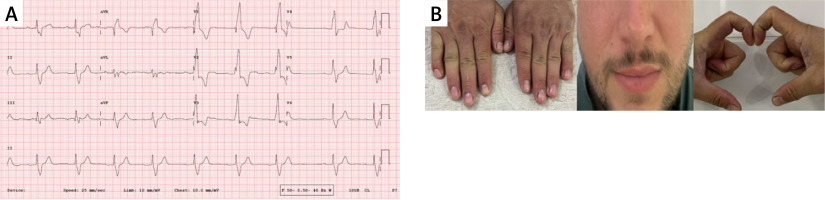

The patient was referred to the outpatient clinic because of non-symptomatic monthly episodes of bradycardia and ventricular extrasystole (less than 1000 beats per day). The patient’s ECG showed a heart rate of 74 beats per minute, a PR interval of 297 ms, right axis deviation and total right bundle branch block. (Figure 1 A) In the physical evaluation of the patient, clubbing was present, but he had no signs of cyanosis, and his functional capacity was NYHA 2 (Figure 1 B).

Figure 1

A – Patient’s admission electrocardiogram. B – Physical examination of patient. Clubbing was present in the patient, who had no signs of cyanosis

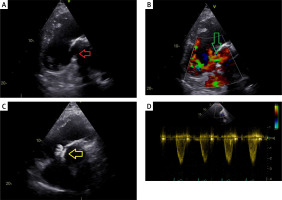

Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed that the left ventricular ejection fraction was 55%, along with right ventricular hypertrophy and impaired right ventricular function. A mean gradient of 91 mm Hg was measured between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery, indicating a significant pressure difference. Additionally, a residual shunt of blood flow was discovered via the VSD. This shunt was thought to be due to the increase in patient size and mismatch of the patch used in surgery (Figures 2 A, B). The heart team decided on percutaneous valve-in-valve implantation and closure of the VSD. Percutaneous surgery was chosen since the patient had undergone open surgery twice before. Thus, open surgery was deferred due to the potential for complications.

Figure 2

A – Ventricular septal defect (VSD) on parasternal long axis view. Red arrow: VSD. B – Green arrow: VSD shunt on continuous wave doppler echocardiography. C – Parasternal long axis view on echocardiography after VSD closure. Yellow arrow: 16-mm muscular VSD occluder (Abbott Vascular). D – Post-procedural transthoracic echocardiography confirmed absence of pulmonary regurgitation; pulmonary valve mean gradient 32 mm Hg

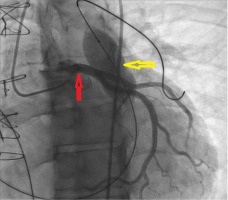

The transcatheter pulmonary valve-in-valve implantation involved accessing the left pulmonary artery using a 0.035-inch Amplatz Super Stiff Guidewire, replaced with a Back-Up Meier Steerable Guidewire. Coronary artery compression was ruled out by performing selective left coronary artery angiography while simultaneously inflating an Atlas PTA balloon of 22 mm × 40 mm in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) (Figure 3). A Melody Valve with a diameter of 22 mm was implanted. A 23 mm balloon was used for post-dilatation. The post-procedure transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed the absence of pulmonary regurgitation, a pulmonary valve mean gradient of 32 mm Hg, satisfactory right ventricular contractility, and no pericardial effusion (Figure 2 D).

Figure 3

Absence of coronary artery compression in the presence of an inflated balloon in the RVOT. Red arrow: coronary arteries, yellow arrow: inflated balloon in the RVOT

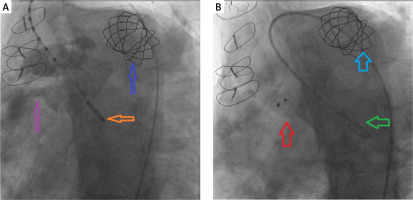

Ventriculography showed VSD (Figure 4 A). The ventricular septal defect (VSD) was crossed in a reverse direction from the aorta using a 0.035-inch Terumo guide wire. The guide wire was captured at the pulmonary artery and pulled out via the femoral venous sheath, also known as the femoral arteriovenous loop. The Amplatzer Muscular VSD Occluder (Abbott Vascular) is a 16-mm device used to close ventricular septal defects. A left ventriculogram and aortogram were performed and did not show a residual shunt through the device (Figure 4 B). Subsequent transthoracic echocardiography confirmed the absence of pulmonary regurgitation and a pulmonary valve velocity of 3 m/s. No residual shunt or aortic regurgitation was detected. The VSD occluder location was confirmed (Figure 2 C). The patient, who was in a stable hemodynamic state, was discharged the following day.

Figure 4

A – Ventriculography showed VSD. Blue arrow: 22-mm Melody valve, orange arrow: Pigtail, purple arrow: VSD. B – Ventriculography showed no residual VSD shunt. Blue arrow: 22-mm Melody valve, green arrow: Pigtail, red arrow: 16-mm VSD occluder (Abbott Vascular)

In this case, the patient underwent earlier surgery for TOF. A second full repair can be performed gradually using transcatheter procedures, such as replacing the pulmonary valve and closing the VSD.