INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019 [1]. Within a few months, this new virus disseminated globally and caused a worldwide pandemic. The disease severity is variable; however, many patients require ventilator support [2]. The weaning of COVID-19 patients from mechanical ventilation is very difficult. Accidental extubation may cause substantial injury or death as well as putting the health care personnel at risk [3].

Generally, tracheostomy is performed in mechanically ventilated, severely ill individuals requiring ventilator support for a longer period. It reduces the requirement for sedation, facilitates tracheal toilet, increases convenience, and decreases the duration of ventilation and hospitalization, which, in an overloaded healthcare system lacking ventilators and skilled medical staff, has a significant impact [4]. However, while tracheostomy allows for smoother weaning, it also entails risks associated with viral transmission [5]. Current descriptive studies regarding tracheostomy in patients suffering from COVID-19 show variable outcomes [6, 7]. The amount of scientific literature discussing tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients is constantly increasing.

In this meta-analysis, we examine the outcomes such as ventilation liberation, decannulation and mortality in patients suffering from COVID-19 who underwent a tracheostomy.

METHODS

This review adheres to the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [8].

Eligibility criteria

In this review, we included all studies where patients with COVID-19 had undergone a tracheostomy. We excluded studies that used extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in COVID-19 patients who had undergone a tracheostomy.

Information sources

The databases PubMed, Google Scholar, and SCOPUS were searched using keywords (“Tracheostomy” [Mesh] OR Tracheostomy) AND (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”). All articles published in these databases up to April 20, 2021, were included.

Study selection

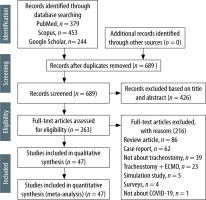

Rayyan QCRI, an online citation screening tool, was used for the management of selected studies [9]. Two authors (A.S. and A.D.G.) separately screened all the titles and abstracts to remove duplicates. In the second stage, two authors independently screened the remaining articles for their full text to consider potential inclusion in the review. Any discrepancies regarding the inclusion of an article were settled by agreement with the third author (P.B.). The process of selection of the articles is described in detail in Figure 1.

Data extraction

The extraction of data was carried out in a standardised format in Microsoft Excel for the following parameters: author, country, sample size, study settings, population characteristics such as age, gender, tracheostomy type, and various outcomes. Two authors (A.S. and A.D.G.) executed data extraction separately (Table 1). Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus with a third author (P.B.).

TABLE 1

Data extraction table

| SN | Author/Country | n | Study settings | Population characteristics | Tracheostomy type | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chao [6], USA (2020) | 53 | Prospective | Mean age: 62.0 ±14.3 years M : F = 33 : 20 | Both PCT = 29 ST = 24 | Decannulation = 7 Ventilation liberation = 30 Death = 6 |

| 2. | Angel [7], USA (2020) | 98 | Retrospective | Mean age: 57 years M: F = 80 : 18 | PCT | Decannulation = 8 Ventilation liberation = 32 Death = 7 |

| 3. | Zhang [14], China (2020) | 11 | Retrospective | Mean age: 66.2 (range 32-93) years M : F = 7 : 4 | Both PCT = 6 ST = 5 | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = Total = 9 Death = 0 |

| 4. | Ferri [15], Italy (2020) | 8 | Retrospective | NA | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 2 |

| 5. | Volo [16], Italy (2020) | 23 | Retrospective cohort | Median age: 69 (42–84) years 21 M, 2 F | ST | Decannulation = 6 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 9 |

| 6. | Riestra-Avora [17], Spain (2020) | 27 | Prospective | PCT, mean age: 67.2 ± 11.7 years ST, mean age: 67.9 ± 9.5 years | Both PCT = 17 ST = 10 | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = PCT = 62%; ST = 55% Death = 11 |

| 7. | Broderick 18], UK (2020) | 10 | Prospective | Mean age: 57.3 | ST | Decannulation = 6 Ventilation liberation = 6 Death = NA |

| 8 | Turri-Zanoni [19], Italy (2020) | 32 | Case series | Mean age: 62 years (range, 32–74 years) | Both PCT = 10 ST = 22 | Decannulation = 1 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 5 |

| 9 | Martin-Villares [20], Spain (2020) | 1890 | Multicentric, prospective observational | NA | Both PCT = 429 ST = 1,461 | Decannulation = 683 Ventilation liberation = 842 Death = 383 |

| 10 | Betancourt-Ramire [21], USA (2020) | 10 | Case series | Mean age: 60.8 years | PCT | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = 8 Death = 0 |

| 11 | Tabaoda [22], Spain (2020) | 5 | Case series | Age range: 63–70 years | PCT | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 2 |

| 12 | Floyd [23], USA (2020) | 38 | Retrospective cohort | Median age: 62 (56–73) years – weaned Median age: 69 (62–79) years – ventilator dependent | ST | Decannulation = 7 Ventilation liberation = 21 Death = 2 |

| 13 | Kwak [24], USA (2020) | 148 | Retrospective | NA | NA | Decannulation = 65 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = NA |

| 14 | Nibbe [25], Germany (2020) | 6 | Prospective | 63–87 years | Hybrid tracheostomy | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 2 |

| 15 | Tornari [26], UK (2020) | 69 | Retrospective cohort | Median age: 55 (48–61) years F : M = 23 : 46 (33.3% : 66.7%) | NA | Decannulation = 35 Ventilation liberation = 46 Death = NA |

| 16 | Piccin [27], Italy (2020) | 24 | Retrospective | NA | ST | Decannulation = 14 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = NA |

| 17 | Temple [28], USA (2020) | 17 | Prospective | Age range: 41–80 years | ST | Decannulation = 4 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 4 |

| 18 | Takhar [29], UK (2020) | 51 | Prospective | > 18 years | PCT = 48 Hybrid = 3 | Decannulation = 3 Ventilation liberation = 4 Death = 2 |

| 19 | Smith [30], UK (2020) | 28 | Prospective | Median age: 55 (48–61) years | PCT | Decannulation = 24 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 0 |

| 20 | Botti [31], Italy (2020) | 44 | Retrospective | Median age: 64 (34–79) years | PCT = 29 ST = 15 | Decannulation = 29 Ventilation liberation = 29 Death = 15 |

| 21 | Picetti [32], Italy (2020) | 66 | Retrospective | Mean age: 58.7 ± 8.7 years 54 M, 12 F | ST | Decannulation = 51 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 9 |

| 22 | Gaspari [33], Brazil (2020) | 31 | Retrospective | Median age of 59 years | NA | Decannulation = 8 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = NA |

| 23 | Zuazua-Gonzalez [34], Spain (2020) | 30 | Retrospective | Mean age: 60.8 ± 8.42 years 22 M, 8 F | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = 7 Death = 17 |

| 24 | Long [35], USA (2020) | 67 | Prospective | Median age: 66 (52–72] years 48 M, 19 F | Both ST = 32 PCT = 35 | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = 52 Death = 5 |

| 25 | Briek [36], UK (2020) | 100 | Prospective | Median age: 55.2 (21–78) years 71 M,29 F | Both ST = 25 PCT = 75 | Decannulation = 84 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 15 |

| 26 | Yeung [37], UK (2020) | 72 | Retrospective | Median age: 58 (51.8–63.0) years 51 M,21 F | Both ST = 44 PCT = 28 | Decannulation = 25 Ventilation liberation = 44 Death = 7 |

| 27 | Hamilton [38], UK (2020) | 530 | Multicentre, retrospective | 405 M,125 F | Both ST = 323 PCT = 217 | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = 244 Death = 62 |

| 28 | Jonckheere [39], Belgium (2020) | 16 | Retrospective | Median age: 62 (58–69) years M 11, F 5 | PCT | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 4 |

| 29 | Ovadya [40], Israel (2020) | 18 | Retrospective cohort study | Mean age: 58 ± 17 years M 15, F 3 | NA | Decannulation = 16 Ventilation liberation = 16 Death = NA |

| 30 | Angamuthu [41], UK (2021) | 55 | Prospective | Mean age 58 (range 29–78) years 37 M,18 F | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 6 |

| 31 | Bartier [42], France (2021) | 59 | Multicentre, retrospective, observational | Mean age: 56 ± 12 years 39 M, 20 F | ST = 54 PCT = 3 Hybrid = 2 | Decannulation = 41 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 6 |

| 32 | Taboada [43], Spain (2021) | 29 | Multicentre, prospective, observational | Mean age: 69.59 ± 8.16 years 18 M, 11 F | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 12 | |

| 33 | Schuler [44], Germany (2021) | 18 | Retrospective, observational | Age range: 42–87 years M 15, F 3 | ST | Decannulation = 5 Ventilation liberation = 10 Death = 6 |

| 34 | Arnold [45], USA (2021) | 59 | Retrospective | Median age: 66 (61–71) years M 40, F 19 | PCT | Decannulation = 34 Ventilation liberation = 38 Death = 20 |

| 35 | Ahn [46], Korea (2021) | 27 | Multicentre, prospective, observational | Mean age: 68.8 (range 26–85) years M 19, F 8 | ST = 20 PCT = 7 | Decannulation = 7 Ventilation liberation = 11 Death = 11 |

| 36 | Cardasis [47], USA (2021) | 24 | Case series | Mean age: 61.1 years M 19, F 5 | ST | Decannulation = 16 Ventilation liberation = 20 Death = 3 |

| 37 | Sebastian [48], India (2021) | 10 | Retrospective | Age range: 38–67 years M 7, F 3 | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = 5 Death = 5 |

| 38 | Archer [49], UK (2021) | 86 | Prospective, observational cohort | Mean age: 56.8 ± 16.7 years | NA | Decannulation = 61 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 7 |

| 39 | Courtney [50], UK (2021) | 20 | Retrospective case series | Mean age 54 ± 8.6 years M 15, F 5 | ST | Decannulation = 12 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 0 |

| 40 | Xu [51], China (2021) | 8 | Case series | Age range 55–74 years | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 6 |

| 41 | Pradhan [52], India (2021) | 12 | Retrospective case series | Age range 22–85 years M 7, F 5 | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = 10 Death = 2 |

| 42 | Mata-Castro [53], Spain (2021) | 29 | Cross-sectional study | Mean age 66.4 ± 6.2 years M 23, F 26 | ST | Decannulation = NA Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 9 |

| 43 | Rovira [54], UK (2021) | 201 | Multicentre, retrospective, observational cohort | Mean age 55.6 ± 11.2 years M 142, F 59 | PCT = 124 ST = 77 | Decannulation = 163 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 29 |

| 44 | Ahmed [55], USA (2021) | 64 | Retrospective, observational cohort | Median age: 63 (54–70) years M 38, F 26 | ST = 48 PCT = 16 | Decannulation = 18 Ventilation liberation = 30 Death = 21 |

| 45 | Sancho [56], Spain (2021) | 11 | Observational cohort study | Mean age: 67.18 ± 6.63 years M 9, F 2 | PCT | Decannulation = 9 Ventilation liberation = 9 Death = 2 |

| 46 | Murphy [57], USA (2021) | 11 | Observational case series | Age range: 25–77 years | PCT | Decannulation = 1 Ventilation liberation = 8 Death = 1 |

| 47 | Rosano [58], Italy (2021) | 121 | Cohort study | Mean age: 65 ± 9 years M 93, F 28 | PCT | Decannulation = 47 Ventilation liberation = NA Death = 55 |

Quality assessment of studies

A critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS tool) was utilised to evaluate the methodological quality of the studies included [10]. It consists of 20 questions with the responses “yes”, “no” or “don’t know”. Two authors independently critically evaluated each article by applying this method. The discussion and consensus settled discrepancies that arose during the critical appraisal. A risk of bias diagram was prepared to represent the quality of the included studies.

Data synthesis and analyses

This meta-analysis focuses on pooling ventilation liberation, decannulation, and mortality rates in COVID-19 patients who have undergone a tracheostomy. The pooled estimates were evaluated using the inverse variance heterogeneity model [11]. The I squared (I2) statistic and Cochran’s Q test were used to test for heterogeneity. Both effect sizes and pooled estimates are expressed as proportions with 95% confidence intervals.

Small study effects such as publication bias were discerned by visual assessment of DOI plots and the Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK) index [12]. Heterogeneity was further investigated using sensitivity analysis. MetaXL software was used for meta-analysis [13].

RESULTS

The records were identified through database searching (PubMed, n = 379, Scopus, n = 453, and Google Scholar, n = 244) using the above-mentioned searched strategy. After removing duplicates, 689 records were analysed. Out of 689 articles screened, 426 articles were removed based on titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 263 full-text studies were evaluated for eligibility. Out of them, 86 were review articles, 62 were case reports, 35 were not about tracheostomy, 23 were on tracheostomy + ECMO, five were simulation studies, four were surveys, and one was not about COVID-19. These were not included. Finally, 47 studies including a total of 4,366 patients were incorporated into the qualitative and quantitative synthesis (Figure 1) [6, 7, 14–58]. Out of them, 12 studies were from the USA, 12 from the UK, seven from Italy, seven from Spain, two from China, two from Germany, and one each from Brazil, France, Belgium, Israel, and Korea. These studies included percutaneous tracheostomy (PCT), surgical tracheostomy (ST), and hybrid tracheostomy. The smallest case series among these included five patients and was reported by Tabaoda et al. [22], while the largest analysis, which included 1890 patients, was performed by Martin-Villares et al. [20]. All studies included adult patients (older than 18).

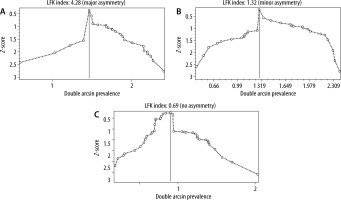

The pooled proportion of ventilation liberation rate was 48% (95% CI: 31–64, I2 = 87, n = 25 studies] (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). There is a high risk of publication bias, as shown by the asymmetrical DOI plot with an LFK index value of 4.28 (major asymmetry) (Figure 3A). Sensitivity analysis did not have a significant impact on the pooled estimate (Supplementary Table 2).

FIGURE 2

Forest plot of ventilation liberation rate after tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients in various studies

FIGURE 3

A) DOI plot of ventilation liberation. B) DOI plot of decannulation. C) DOI plot of mortality rate

The pooled proportion of decannulation rate was 42.0% (95% CI: 17–69, I2 = 95, n = 31 studies] (Figure 4, Supplementary Table 3). There was a moderate risk of publication bias as seen in the DOI plot with the LFK index value of 1.32 (minor asymmetry) (Figure 3B). The sensitivity analysis shows no significant impact on the pooled estimate (Supplementary Table 4).

The pooled proportion of hospital mortality was found to be 18% (95% CI: 9–28, I2 = 84, n = 41 studies] (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 5). This can be considered a reasonable estimate of the available data due to less risk of publication bias as seen in the symmetrical DOI plot with an LFK index value of 0.69 (no asymmetry) (Figure 3C). Sensitivity analysis also did not appear to result in a significant change in the pooled estimate (Supplementary Table 6). On subgroup analysis, no significant difference was found in mortality between the PCT (17%; 95% CI: 6–30, n = 14 studies) and ST subgroups (19%; 95% CI: 12–27; n = 19 studies]. The risk of bias is presented in Supplementary Table 7. In most of the reviewed articles, no spread of the disease among health care staff engaged in tracheostomy procedures was reported.

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 patients can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and pneumonia [59]. A substantial number of critically ill patients may require sustained mechanical ventilation. Many harmful effects, e.g. ventilator-associated pneumonia and the disuse myopathy, are related to prolonged mechanical ventilation. Tracheostomy is usually performed in individuals who need mechanical ventilation over long periods. The rising number of severe COVID-19 patients led to an imbalance between the volume of patients requiring intensive care and ICU beds and infrastructure provision [60]. As a result, the tracheostomy can provide a crucial measure for individuals’ earlier discharge from the ICU to general care wards. Patients who are at the hospital with tracheostomy and do need mechanical ventilation can be managed with limited sedation in relatively low-intensity wards [61].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the second systematic review and meta-analysis of the results of tracheostomy in patients suffering from COVID-19. In the previous meta-analysis of tracheostomy outcomes in COVID-19 patients by Benito et al. [62], 18 articles were included up to September 27, 2020. They found the pooled cumulative incidence of mortality to be 13.1% (95% CI: 8.5–18.4%) in these patients. Similarly, the present meta-analysis of 47 articles showed the mortality rate of 18% (95% CI: 9–28) in COVID-19 patients who have undergone a tracheostomy. Also, Shah et al. [63] noted a mortality rate of 19.2% in 113,653 tracheostomies in non-COVID-19 patients.

Benito et al. [62], in their meta-analysis, reported the cumulative incidence of decannulation as 34.9% (95% CI: 25.4–44.9%) and the ventilator weaning in patients with COVID-19 with tracheotomy as 54.9% (95% CI: 47.3–62.5%). In our meta-analysis, the rates of decannulation and ventilation liberation were 42% (95% CI: 17–69) and 48% (95% CI: 31–64), respectively.

Tracheostomy is an aerosol-producing surgery and can increase the risk of COVID-19 dissemination to healthcare staff [64]. In all the included studies, healthcare personnel (HCP) wore personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect against airborne, contact, and droplet exposures during the procedure [65]. In most of the articles, it is specifically mentioned that there were no cases where health care workers acquired COVID-19 infection after performing a tracheostomy in an infected patient. Out of 47 studies, only one study has reported COVID-19 infection in HCP performing tracheostomies. Angamuthu et al. [41] reported that out of 72 HCP who performed a total of 71 tracheostomies, eleven (15%, 11/72) had COVID-19 symptoms. Ten of these HCPs underwent a COVID-19 test, of whom three tested positive. However, none of the HCP required hospitalisation. This demonstrates that HCP can safely perform tracheostomies in COVID19 patients.

Tracheostomies can be performed at the bedside without the patient being transferred to the operating room [32]. This is cost-effective and is linked to a lower risk for other patients and healthcare workers during the pandemic. Most of the included studies showed that most tracheostomies were either without complications or with minimal complications (especially minor bleeding). The minor bleeding can be associated with the use of low molecular weight heparin in most COVID-19 patients as a part of the treatment protocol [66].